IT IS WELL LISTEN NOW

The Story and Sound of “It Is Well”

Great songs have a way of communicating the complexity of deep emotions musically and It Is Well With My Soul has stood as a standard model of this reality. For over a century, From church pews and hospital rooms, to funerals and weddings, this hymn has pointed many to the peace of Christ in the midst of suffering. But behind the timeless lyrics lives a deeply human story of loss, collaboration, and the way music gives voice to faith.

A Prosperous Life, Interrupted

Horatio Gates Spafford was a man who seemed to have it all. Born in 1828, he became a distinguished lawyer in Chicago who gained substantial wealth through investing heavily in real estate during the city’s booming developmental years. He seemed to embody the American success story, wealthy, respected, a devoted husband and father, and a committed Presbyterian layman who supported church ministries and even the evangelistic campaigns of Dwight L. Moody.

But in 1871, tragedy began to strike. His son died of scarlet fever at only 4 years old. That same year, the Great Chicago Fire devastatingly destroyed a good amount of the city including much of Spafford’s property and financial security. Even after facing all of this heartbreaking loss he and his wife chose to keep trusting God leaning into their faith.

Two years later, Spafford arranged for his family to travel to Europe for rest and to assist with Moody’s revival meetings. Business delayed his travel so his wife Anna and their four daughters–Annie, Maggie, Bessie and Tanetta–set sail ahead of him on the French steamship Ville du Havre. Midway across the Atlantic, the ship collided with another vessel and sank in twelve minutes. Anna was pulled unconscious from the wreckage, but all four daughters tragically drowned. Her telegram from Wales bore the chilling words: “Saved alone. What shall I do?”

From Grief to Song

When Spafford crossed the Atlantic soon after to join Anna, the captain of his ship called him to the deck when they passed the approximate place where the Ville du Havre had gone down. There, above the waters that became his daughters’ graves, Spafford wrote the opening lines of It Is Well With My Soul.

The hymn does not shy from sorrow–its very first stanza says that “sorrows like sea billows roll”–yet it insists on peace from God being “taught.” The lyrics are not born from denial but from a profound theology of hope: that even when life collapses, the soul can be steadied by Christ’s redeeming work.

The story of Horatio Spafford echoes the ancient questions posed in the book of Job, long considered wisdom literature. Job wrestles with the raw problem of suffering–why the righteous endure pain and loss if God is good? Even today it stands as a common hurdle for those who profess Christ and those who don’t. Apologetic responses have been articulated over the years to contend with this “problem of suffering,” but I have come to find that questions like this aren’t best satisfied by intellectual exchange, but humble faith and trust in God’s sovereignty.

Spafford’s hymn stands in that same tradition, not offering neat explanations but embodying a lived wisdom that can only be forged in grief. Just as Job’s declaration, “Though he slay me, yet will I trust in him,” rises from the ashes of devastation, "It Is Well With My Soul” proclaims that peace is still possible when the soul is anchored in God’s steadfast love.

Collaboration as Sacred Work

Spafford gave the world his words, but the hymn would not have become what it is without the composer Philip Bliss. Bliss, one of the era’s great gospel composers, set Spafford’s text to music and named the tune ‘VILLE DU HAVRE’ in honor of the tragedy. His melody begins tender and contemplative before rising to a triumphant refrain–musically enacting this journey of grief to conviction.

This cooperative effort is part of what makes the hymn endure. Alone, Spafford’s words might have remained private reflections but with Bliss’ melody, they became a communal anthem the church could sing together. Hymnody at its best is born in collaboration–lyric and musical composition intertwined to carry truth across time.

Singing It Until We Believe It

Strictly speaking, “It Is Well" is considered a gospel song rather than a hymn, because of its refrain: “It is well, it is well with my soul.” Refrains are central to gospel tradition–repetition designed for participation, a way for congregations to “sing it until they believe it.” Each return to the refrain is a declaration that peace is possible, even when storms rage.

“It Is Well” Reimagined

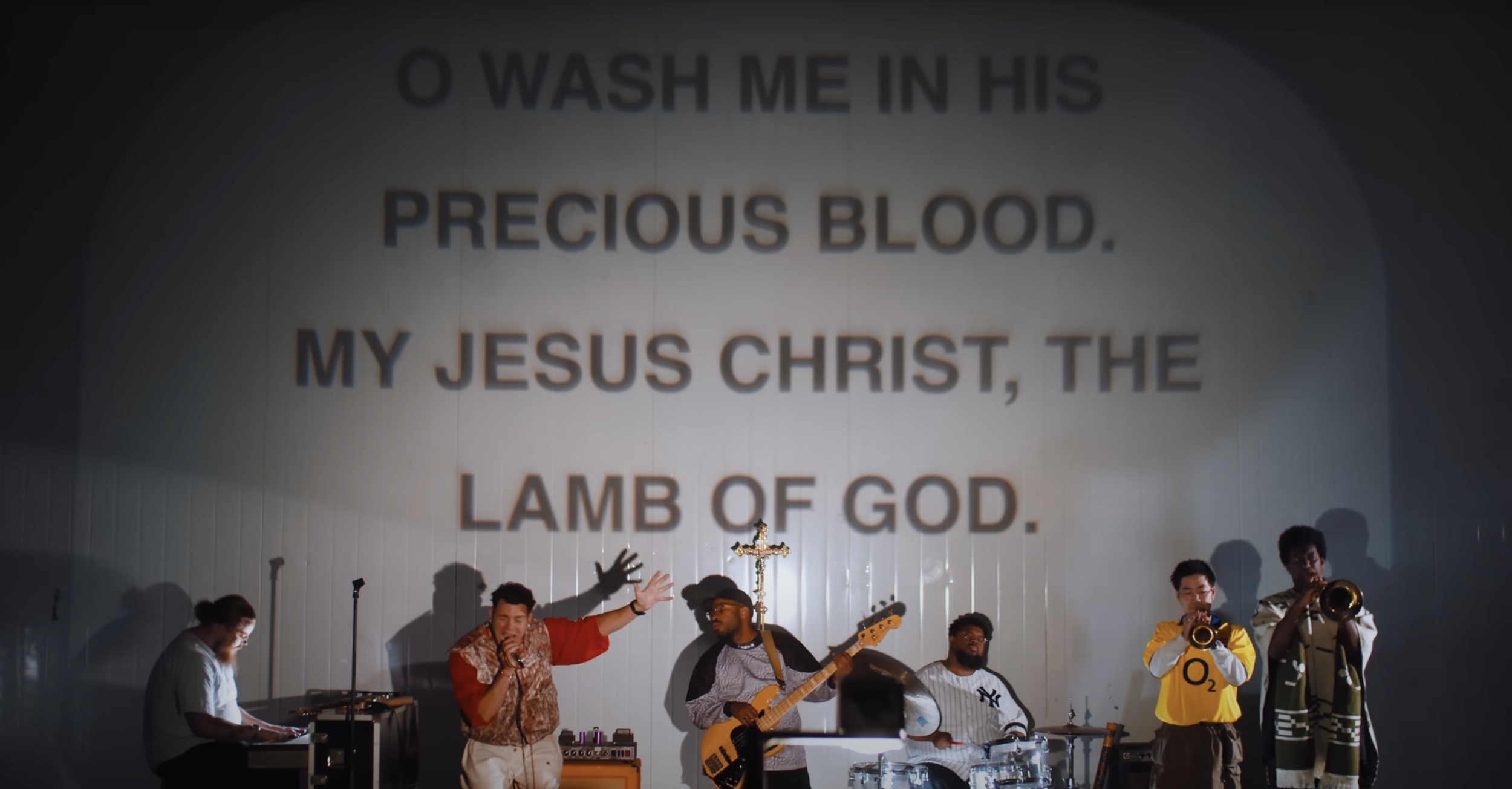

That same duality–storm and stillness–inspired our reinterpretation with Kings Kaleidoscope. In our remix, we wanted to return to the band’s roots: a room full of friends reworking hymns together, not pieced together on screens but lived in the air of a room.

Chad sat at the reed organ and played the rising chord progression with its breathy tone being the backdrop to his patient vocal performance. JJ crafted a delicate ‘lullaby-like’ arpeggiated line on his short scale guitar using flatwound strings and baritone tuning. Zach offered piano parts that dance and respond to the space the guitar leaves, while I also attempted to add to this waltz-like feeling with slow walking bass parts. You may notice there are no drums or percussion in this arrangement so all of the rhythm truly is held down by this ‘swaying’ musical approach compositionally. The sound that resulted feels almost like the lilt of the sea itself–waves rising, rocking, subsiding.

Brian took the song to the finish line building upon the studio performance from the band at “Kamp Kaleidoscope” earlier this year. His added orchestral arrangement gives the song intense dynamic range building as the song progresses. Finally beautiful chaos is reached at the last verse which then breaks into calm sailing for the final refrain.

I feel like the band agrees that what has emerged from this rendition is not simply a modern cover, but an ode to the original spirit of the hymn: music born from loss, reshaped through community, and lifted into hope. Just as Spafford and Bliss combined words and melody to give the church a voice for sorrow and peace, our collaboration seeks to inhabit that same space–a reminder that when all else fails, the refrain still holds true: “It is well with my soul.”

-John McNeill (Bass & Theology)

AMAZING GRACE LISTEN NOW

“A Theology oF TRANSFORMATION”

Few hymns have left as deep and lasting an impression as “Amazing Grace.” Sung in churches, at funerals, in protest marches, and across generations, its words are familiar to millions. But behind it for many it is a story of tension and paradox, a balm for the oppressed, first written by a man who once held the whip. Grace knows no bounds and John Newton was a prime example of it.

Born in London in 1725, John Newton grew up under the guidance of his devout Christian mother, Elizabeth. She introduced him to the Bible and taught him hymns from an early age, instilling in him a spiritual foundation. Yet her influence was cut short when she died of tuberculosis while Newton was still a child. Left in the care of his father, a merchant sea captain, Newton was drawn into the life of a sailor, being forced to join the Royal Navy.

He soon found himself aboard the HMS Harwich where his continued poor behavior got him into trouble. He tried deserting and was flogged and publicly demoted in front of the crew. Eventually the captain had Newton transferred to a slave ship bound for Guinea. It didn’t take long for Newton to find himself chained on the deck of this new ship as a captive with very little food. The crew on the Pegasus were also not fond of Newton and consequently he was left in West Africa in a slave trader’s possession.

His father sent for help and had him rescued only to board the Greyhound where he and the crew found themselves fighting for their lives in a storm. During this catastrophic storm Newton and the crew thought they would all die, in a moment of desperation Newton prayed to God for help. Miraculously the storm eventually stopped and they landed in Ireland where he formally dedicated himself to the Lord. Though far from an immediate transformation, it marked the start of a lifelong spiritual journey. However, the troubling backdrop and sentiments of the times showed that Newton's Christianity, like much of Europe’s at the time, had room for both Jesus and shackles.

In time, he found himself aboard ships involved in the transatlantic slave trade. Serving as a first mate and later a captain, Newton played a direct role in transporting enslaved Africans—contributing firsthand to the cruelty and dehumanization that defined the trade. Though he would later recount this time with deep regret, he continued in it for years, unaware of the full spiritual and moral cost.

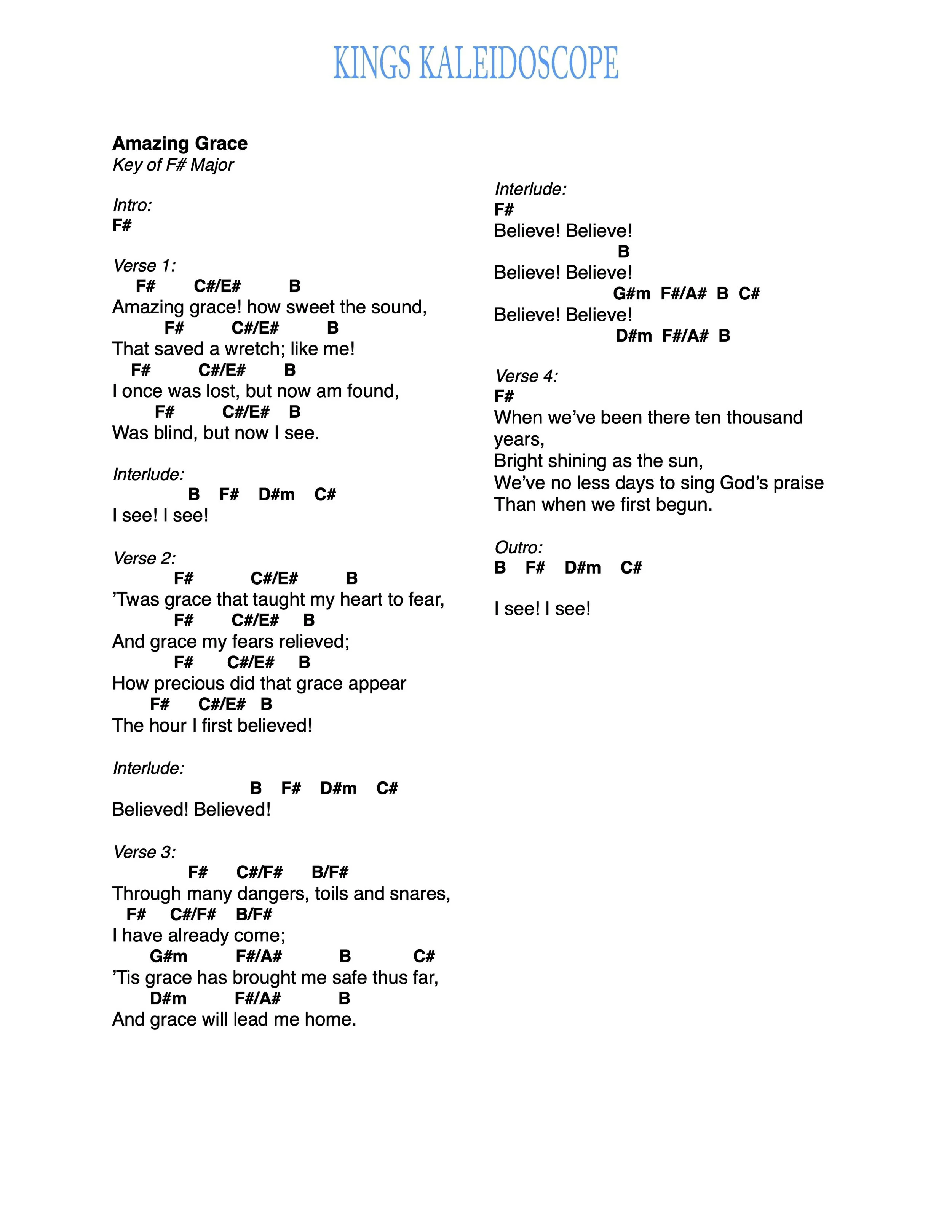

By 1754, ill health brought Newton’s sailing career to an end. Encouraged by friends and mentors, he pursued ministry in the Church of England and was ordained in 1764. He became the parish priest of Olney, where he would serve for many years. It was there that he began writing hymns in collaboration with poet William Cowper. Their collection, Olney Hymns (1779), included “Amazing Grace,” originally titled “Faith’s Review and Expectation.”

Written to accompany Newton’s New Year’s Day sermon in 1773, the hymn draws on his own spiritual journey. The lyrics—“I once was lost, but now am found; was blind, but now I see”—speak to his personal experience of redemption. They also echo biblical themes of forgiveness and transformation, drawn from passages such as 1 Chronicles 17 and Ephesians 2.

In the decades following his conversion, Newton became increasingly vocal in opposing the slave trade he had once supported. In 1788, after years of silent reflection, he published Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade. In it, he described the horrors he had witnessed and expressed deep remorse for his role. “It will always be a subject of humiliating reflection to me,” he wrote, “that I was once an active instrument in a business at which my heart now shudders.”

Newton’s testimony became a valuable voice in the growing British abolitionist movement. He mentored and encouraged William Wilberforce, a Member of Parliament who would become one of the leading figures in the campaign to end slavery. Newton’s firsthand account of the trade’s cruelty helped influence public opinion. In 1807, the British Parliament passed the Slave Trade Act—abolishing the transatlantic slave trade throughout the British Empire. Newton died later that year, having witnessed the brief fruit of the cause to which he had devoted his ministry life.

“Amazing Grace” has outlived its author by centuries. Though written from one man’s personal reflection, it has resonated with communities far beyond Newton’s world. It has been sung by enslaved people in America, by Civil Rights marchers in the 1960s, and by mourners at memorials around the globe. The hymn’s message of grace, repentance, and hope continues to offer comfort and strength in times of trial.

John Newton’s life is not one of moral perfection, but of transformation. His story invites us to grapple with the tension between human failure and divine mercy. Through his words and his witness, we are reminded that no one is beyond the reach of God’s grace—and that redemption, though sometimes slow, is always possible.

-John McNeill (Bass & Theology)